Publisher’s Note: This column is the second in a series by Don Lenihan exploring the issues around the use of AI, including the social, economic and governance implications. To see the first in the series, click here.

Are you part of the estimated 6.5 million Canadians who don’t have a family doctor? I’m not, but it still takes me three to four weeks to get an appointment. Meanwhile, I must rely on Dr. Google (who can’t even write me a prescription). Are there better options?

Well, if things get bad enough, I could go to emergency – where I’d sit in the waiting room for six hours (if I’m lucky) to see a doctor. And there’s always the nuclear option: call an ambulance and you get to see a doctor right away. But that’s about it.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m a fan of our publicly funded healthcare system, but I’m worried about how badly it’s listing under the strains of doctor shortages, inefficient operations, and more. For all the billions of dollars governments have invested in it, no one seems able to right the ship.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a ray of hope. Remarkable new tools are emerging that could greatly improve diagnostics, treatment, and efficiency. These are cornerstones of a so-called “learning” healthcare system, which could transform service and care. Let’s consider how new AI tools could help reduce wait times.

AI Personal Assistants – An iPhone Moment?

Last week, both OpenAI and Google released demos of chatbots that sounded indistinguishable from the humans around them. They joked and bantered like real people, trading information and anecdotes.

These bots can now search our emails, photos, and files, remember past conversations, and use these materials to build up a complex, highly personalized profile of us – hence the “personal” in “personal assistant.”

But there’s even bigger news: personal assistants, we’re told, will soon do more than process data. They’ll use what they learn to execute tasks for us, such as ordering our groceries, managing our agendas, and paying our bills.

Basically, chatbots are poised to engage with the real world. (We’re not told exactly when, but the rumour is 12-18 months.) If so, this could be a watershed moment that thrusts AI to the centre of everyday life, much like the iPhone did for the internet in the 2000s.

This would also transform businesses: AI assistants could make appointments, fill orders, respond to complaints, purchase goods, and much more. Humans won’t be just chatting and joking with them; we’ll be assigning them tasks.

Healthcare too would be a big winner. AI assistants could take on a wide range of tasks in doctors’ offices, clinics, and hospitals, such as scheduling appointments, processing insurance claims, managing medical inventory, and ensuring consistency in the quality of care. They could streamline, manage, and execute administrative tasks with speed, competence, and accuracy.

This, in turn, would be a big help with wait times. According to recent reports, family doctors in Ontario spend about 19 hours a week doing paperwork, which contributes to burnout and discourages new medical graduates from entering family medicine.

AI in Diagnostics: Med-Gemini

But even if personal assistants take on these tasks, that will get us only partway to solving the wait times issue. We also need more doctors – and for this, we must turn to another AI tool and a different task: diagnostics.

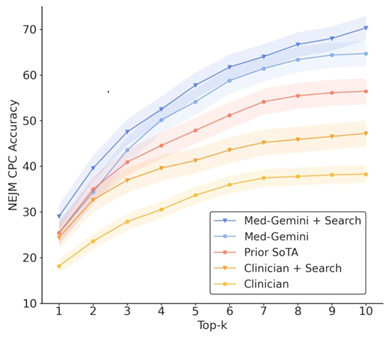

Consider Google’s Med-Gemini: it analyzes medical images (such as X-rays) and electronic health records to provide expert diagnostic advice. The system not only scored a 91.1% on a key medical exam but, as the graph below shows, did significantly better at diagnosing cases than both GPs and specialists. When real-time data searches were included, it scored even higher:

Med-Gemini may not be a human doctor, but it can perform many of the same tasks. Moreover, tools like this are growing more powerful, accurate, and diverse by the day. (Med-Gemini can already analyze genetic, environmental, and lifestyle data to suggest personalized treatment plans.) And the better they get, the more of a physicians’ workload they can assume, helping to reduce wait times, put diagnostic accuracy on a steep upward curve, and even perform “house calls” via the internet.

The Importance of Health Data

Lastly, let’s note that to do a good job of diagnosing illnesses, fixing bottlenecks, or renewing prescriptions, AI tools need high quality data – and lots of it. Data tells them what to do.

Unfortunately, our health data is currently scattered across myriad systems and silos, often making it impossible for these tools to get the data they need. AI companies are building other tools to address this issue.

For example, Apple Health Records integrates health records from multiple providers, facilitating seamless data sharing and better-coordinated care.

But tools like this are useful only if patients, doctors, hospitals, and governments agree to share their health data with one another. And that could be a problem. If Canadians or their governments refuse, they could scuttle AI-led efforts to build the infrastructure for a learning system.

Policy and Politics

So, powerful new technologies are available that could help revolutionize our healthcare system. But to get the optimal result, we must put them to the right use. Our analysis points to at least three critical challenges on the horizon:

- Jobs: Healthcare workers may fear that AI assistants will replace them.

- Professional Concerns: Medical associations may worry that AI diagnostic tools could overshadow human doctors.

- Privacy: Patients and governments may resist sharing their data due to privacy concerns.

If Canadians want their healthcare system to transition to the AI age, these challenges must be resolved. Policymakers must find ways to ensure that AI supports medical staff and respects privacy, while also ensuring that AI tools can work together, efficiently and effectively. The tools are there; now the question is, do we have the vision and the will?

Don Lenihan PhD is an expert in public engagement with a long-standing interest in how digital technologies are transforming societies, governments, and governance. This column appears weekly.